The Holy Script and Speech

There is a beraisa quoted in mesechtos Megillah (3a) and Shabbos (104a) that R’ Chisda says, “the [final] mem and samech of the luchos stood miraculously.” Meaning: the letters were carved all the way through, so that ם and ס, letters that are drawn as closed shapes had a piece in the middle unattached to rest the luchos. The miracle was that the unattached middle piece floated in place with the rest of the luchos.

Rav Chisda’s statement describes the current block script and kesav Ashuris (Assyrian script / praiseworthy script; see below) used in sifrei Torah, tefillin and mezuzos. Which would indicate that Rav Chisda kesav Ashuris is at least as old as Har Sinai, and the original script the Torah was given in.

Another argument in favor of the age of kesav Ashuris is Menachos 29b, the famous medrash of Moshe Rabbeinu’s visiting Rabbi Aqiva’s class, and witnessing R’ Akiva proving “heaps of laws” from the crowns atop the letters. Ashuris is the script that has such crowns.

The halachic requirements also argue in its favor. Note that we require Ashuris down to the qutzo shel yud — the thorn on the yud (understood by most to be an extension of the bottom left corner). This law has a parallel in tefillah. You fulfill the Torah law of davening if you say “haKel haqadosh” at the end of the third berakhah of the Amidah during the 10 Yemei Teshuvah. After all, the Torah requirement doesn’t require any particular text. But the Great Assembly can require repetition of the Shemoneh Esrei over this mistake. The holiness of a seifer Torah requires many many laws specific to Ashuris. It is one thing to say that they require a more specific prayer than Hashem did, or even a more specifically written Torah than Hashem did, but do Rabbis have the power to abrogate holiness that HQBH gave? If the Torah was not originally given in Ashuris, there is no qutzo shel yud on Moshe Rabbeinu’s original manuscript!

But the Yerushalmi’s version of the gemara in Megillah (1:9), has R’ Levi quoting Mar Zutra and R’ Yosi that it was ayin and tes that had floating pieces. This would fit kesav Ivri (Hebrew script, see candidates below), although Ivri also has other letters that are closed shapes. Perhaps it refers to yet another script, but it’s certainly not Ashuris!

Proto-Sinaitic |

Phonecian |

The core discussion of the script is really in Sanhedrin (21a-22b). It opens with Mar Zutra, one of the possible sources in the Y’lmi for ayin vetes, saying:

Bitechilah nitenah Torah leYisrael bikesav Ivri velashon haqodesh.Chazrah venitenah lahem biymei Ezra bekesav Ashuris velashon Aramis.

Originally the Torah was given to Israel in Ivri script and in the holy language. It was returned and given to them in the days of Ezra in Ashuri script and in Aramaic.

However, we chose Lashon haQodesh and Ashuris, leaving the other language and script for the hedyotos (usually: commoners).

Rav Chisda, our source for mem vesamech, explains Mar Zutrah — who until now I had assumed was the other side of the machloqes. He says that “hedyotos” here are the Kusiim (a heterodox group of uncertain Jewishness; probably a major component of today’s Samaritans — who do use Ivri script today), and kesav Ivri is “Libunah“. Rashi identifies Libunah as a script used in qemei’os and [the extra-halachic portions of] mezuzos.

The question as I see it is whether we can assume that if R’ Chisda explains a position we can conclude he holds like it. Beis Hillel, for example, was known for first explaining the shitah of Beis Shammai that they rejected. Alternatively, this could be a proof for the Radvaz, that there really is no dispute.

The amora’im in mesechtes Sanhedrin take three positions:

1- R’ Yosi holds that the use of Ashuris was a new institution in Ezra’s day. And Ashuris is so named because it was brought over from the land of Ashur (Assyria).

That view also seems to be the one of a medrash quoted by a number of rishonim on the beginning of Yonah. There the person Ashur is credited with not participating in the Tower of Bavel for which he received two gifts: His children were given a second chance in the days of Yonah (who was sent to Nineveh, the capital of Assyria), and kesav Ashuris.

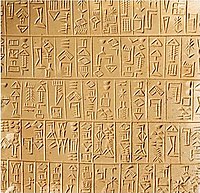

The archeological problem is that the people of Assyria spoke Akkadian and Sumerian, both of which we have records of only in Cuneiform, not Ashuris.

2- Rebbe holds it’s a case of chazar veyasdum — the knowledge was lost, and the Anshei Keneses haGedolah (AKhG), reestablished it. The name of the script, Ashuris, is from the same root “ashrei“, praiseworthy. (This is also the etymology found in the Rambam.)

Perhaps this is the same chazar veyasdum mentioned in the same TB Megillah, in which AKhG restored the final forms of the letters (םןץף”ך). Which works even more smoothly if Kesav Ivri has no finals.

3- R’ Shim’on ben Elazar, and a mass of others, give the final opinion. The two factors, number and finality, leads a few rishonim to decide that this is the gemara‘s conclusion. The script was always used in sacred texts. Rather, it was only popularized for other writing in Ezra’s day.

The Ridvaz (Rabbi Yaakov Dovid Wilovsky; Rosh Yeshiva of Slutzk; b. Kobrin, Russia 1845 – d. Tzefas 1913), in his commentary on the Yerushalmi, suggests that there is no dispute between the two talmuds on this point. The first luchos were in Ashuris, and after the loss of holiness caused by the Golden Calf, the second pair were given in kesav Ivris. The Bavli cited a quote about the former, the Yerushalmi, about the latter.

The Ridvaz’s resolution would lead to the state described by Rav Shim’on ben Elazaer et al as well. It would mean that the sacred Ashuris was known to only a few. Only Moshe saw the first tablets unbroken — possibly Yehoshua caught a glimpse. But the masses were given the second set, the one in Ivris.

It would also explain the use of the words “nitenah Torah leYisrael” rather than simply “nitenah Torah“. Because Mar Zutra in Sanhedrin is discussing how it was given to the masses, to “Yisrael” as a whole rather than only the intelligentsia. If understood this way, then the reference to Aramaic is that the masses in the days of Ezra, speaking Aramaic and not Lashon haQodesh, were given a targum. However, no one proposed changing the language of the text itself. (What would happen to derashos, the derivation of halakhah through textual analysis, if that really were the proposal?)

Last, it would explain why Daniel would be able to read the writing on the wall, while most people could not — it was in Ashuris!

How do the mekubalim, who place so much emphasis on the shapes of letters, understand R. Yosi’s opinion? It would seem that the shapes of the letters are an integral part of Torah’s (original, intended) meaning according to the mekubalim.

I don’t know. A good question to raise on Avodah.

I also don’t know if mequbalim would equate “original” with “intended” meaning. After all, they believe in progressive revalation of aggadic truths, no?