Aristotle, Science and Halakhah

ר’ יצחק בי רבי אלעזר שאל זרק מרשות היחיד לרשות הרבים ונזכר עד שהוא ברשות הרבים. על דעתיה דר’ עקיבה יעשה כמי שנחה בר”ה ויהא חייב שתים. א”ר חונה לא חייב ר’ עקיבה אלא ע”י רה”י השנייה. רבי אבהו אומר בשם ר’ אלעזר בשם ר’ יוחנן היה עומד בר”ה וזרק למעלה מעשרה. רואין שאם תפול אם נחה בתוך ד’ אמות פטור ואם לאו חייב. והתני שמואל מרה”י לרה”י ורה”י באמצע רואין שאם תפול נחה בתוך ד’ אמות פטור ואם לאו חייב. תמן את אמר אין ר”ה מצטרפת. והכא את אמר ר”ה מצטרפת. א”ר חונה תמן שאם תפול קרקע שתחתיה רשות היחיד. ברם הכא שאם תפול קרקע שתחתיה רשות הרבים.Rabbi Yitzchaq of Rabbi Eliezer’s beis medrash asked: If someone threw an item from a private domain to a public domain [on Shabbos, while unaware either that it was Shabbos or that he was about to violate Shabbos] and remembers before the item enters the public domain. By the reasoning of Rabbi Aqiva, it should be made to be like someone who put it down in the public domain, and he should be obligated in two [sacrifices for violating Shabbos through forgetfulness]. Rabbi Chunah said: Rabbi Aqiva would not obligate except if it went through a second public domain.

Rabbi Avohu says in the name of Rabbi Elazer, in the name of Rabbi Yochanan: Someone who was standing in a public domain and through an item above 10 [tefachim]. We see if it would fall. If it would come to rest within 4 amos , he would not be culpable [although he did violate Shabbos rabbinically — patur aval assur]. And if it would not, he would be culpable [because enough was already done in error to require the offering].

But didn’t Shemuel recite the teaching that [something thrown] from private domain to private domain with a public domain between them, we look to see if it were to fall, whether it would be within 4 amos [of the first private domain, the thrower] would not be culpable, but if not, he is culpable? Over there [in our original case] you say the public domain does not connect [to the private one], but over here [in Rav Avohu’s case] you say a public domain does connect?

Rabbi Chuna said: Over there is a case where if it were to fall, the ground under it is private domain. Whereas over here if it were to fall, the ground under it was [already] public domain.

The numerous amoraim in this gemara, most clearly Rabbi Chuna’s second statement at the end of my quote, assume that when an object falls, it falls down to the ground it is directly over. Not as Newton showed, that a thrown object follows a trajectory, a parabola.

Which means that this page from last week’s daf yomi gives me an excuse to discuss Aristotelian physics and whether it should still play a role in Judaism. I visited the topic once before, in my discussion of the Rambam’s understanding of mal’akhim.

According to Artisotle, action starts with an intellect. The intellect moves an object by imparting impetus to it. Since no one had separated out the concept of friction (including air drag), there was no law of conservation of impetus; it’s not just another word for momentum. So, eventually impetus would run out, and the object would stop moving. This is why Aristotelians, including the Rambam, believed that the spheres (the stars, planets, sun and moon, or the transparent spinning shells in which they are embedded and which give them their paths in the sky) were intellects. Similarly, this is the role of angels — they are the chain of intellects necessary to turn G-d’s Will into physical action.

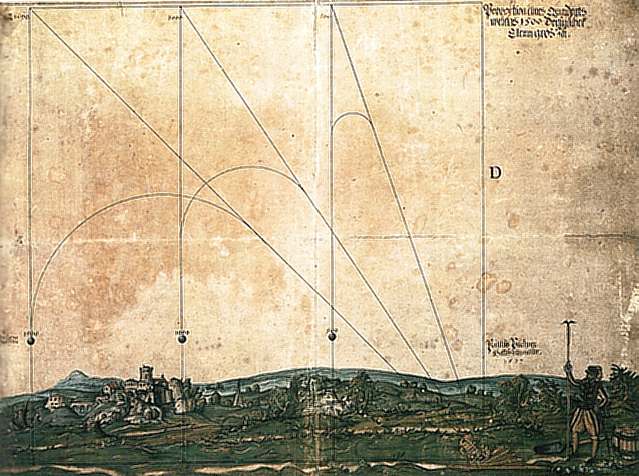

In the case of a thrown object, Aristotelian physics would expect the object to move diagonally upward in the direction thrown, go through a short curve as the impetus runs out, and then the object would fall straight down. Something like this:

This is clearly also what our amora’im expected when they discuss where the object would land if it would fall right then. As opposed to Newton’s model, where the object would continue along the parabola, landing beyond where it was at the moment the thrower remembered it was Shabbos.

“Cartoon physics”, the world as drawn by animators, also usually assumes that thrown objects — or characters who run off cliffs — follow Aristotelian trajectories, not Newtonian parabolic ones. Why is that relevant? Because it says something about Aristotelian physics and how it relates to instinct. Aristotle didn’t experiment and systematize the results. He made a system out of the results of how the world should work by speculation. He performed “Natural Philosophy”, not “Science”. Thus, many of his results match our instincts, particularly in cases where they don’t match reality.

How this disjoin between our expectations and reality plays out in professional baseball players is interesting. On the one hand, they must have learned with some part of their minds the true path of the ball, because they do manage to be in the right place at the right time. On the other, they still slip into the language of “getting under the ball” as though being directly under the ball is relevant. Here’s a psychologist’s description, from “Going, Going, Gone! The Psychology of Baseball” by Ian Herbert in the April 2007 issue of the Association for Psychological Science’s journal, “Observer”:

Like hitting, fielding also seems like it should be a mental and physical impossibility — which makes it fascinating to psychology researchers. If you put a player in the outfield and make him stay put, he is actually quite bad at predicting where a ball is going to land, yet he will run effortlessly to that spot when allowed to do so. How?

One of the first theories developed to explain fly-ball catching was developed by physicist Seville Chapman, who hypothesized that fielders used the acceleration of the ball to help them determine where the ball will land. To simplify the problem for experimental purposes, balls were only hit directly at the fielders, who then moved either forward or backward in order to keep the ball moving at a constant speed through their field of vision — so, they started with their eyes on home plate and then moved in a way that kept their eyes moving straight up at a constant speed until they made the catch. If they moved too far forward, the ball would move more quickly through their field of vision and go over their head. If they moved too far backwards, the ball would appear to die in front of them.

This theory seemed too simple to Mike McBeath, a psychologist at Arizona State. For one thing, Chapman’s model predicted that fielders would use the same process for balls hit to their left or right, simply making a sideways calculation along with the basic speed calculation. But that would mean balls hit to the side should be harder to catch, and McBeath (and every sandlot outfielder) knows that’s simply not the case. Any outfielder will tell you that a ball hit directly at him is the most difficult to catch, so McBeath reasoned instead that, when a ball is hit directly at a fielder, the fielder lacks some crucial bit of information for making the catch.

He came up with a method that was similar to Chapman’s but included an extra piece: He hypothesized that fielders kept the ball moving through their field of vision in a straight but diagonal line. So if the outfielder is looking at home plate when the ball is hit, he then keeps his eyes on the ball and runs so his head moves along a constant angle until the ball is directly above him, which is when he snags it. To test this, McBeath had fielders put video cameras on their shoulders, and the cameras moved in this manner.

Yet ask any Major Leaguers about this, and you’ll get blank stares. McBeath did talk to pro outfielders, and responses ranged from “Beats me” to “You’re full of it.” That’s because there’s no conscious processing involved; it’s all taking place at the level of instinct, even though the geometry is sophisticated.

I see, therefore, two possible resolutions to how to deal with our gemara given the advances in science.

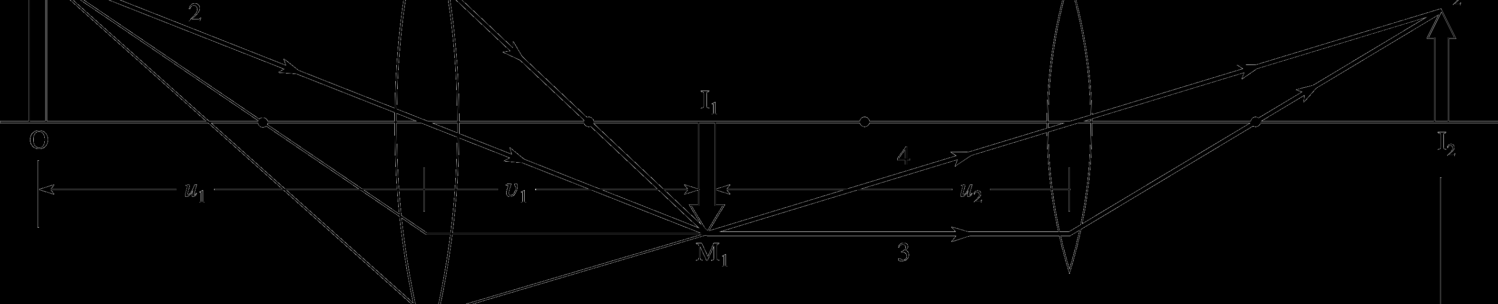

1- One can fit the amoraim to Newton. What causes the parabola? Well, there are three forces acting on the object: the throw of the hand, the pull of gravity, and the drag of the air it is flying through. If we are trying to isolate what the person did during the period of forgetting, we should mentally “shut off” the throw of the hand at the moment they remembered it was Shabbos. In which case, the remaining forward motion that happens after remembering isn’t part of the forgotten action, and could be ignored. We pretend as though it were to fall straight down, without the vector added by his hand. This notion that it’s a pretense isn’t in the gemara, but there is no reason to believe that such a fiction (pretend the momentum disappeared) vs. thinking it would really occur is relevant to the halakhah.

2- Taking a major step back, we can ask whether the halakhah actually depends on the science. After all, the role of halakhah is to refine our souls. (Connect to G-d, ennoble ourselves, perfect our middos, our thought, however you define the refinement.) In the posts in this category I have argued that this implies that illusions are no less relevant than reality, and innate expectations of how the world works more important than how it really does.

If we are so hard-wired to think that objects move in a certain way, such that even professionals who rely on predicting where a thrown object would be cannot fully escape it — isn’t that the reality halakhah must address? Which approach to throwing an object in a public domain better relates to the person’s responses, more closely addresses the forces that shape him: Newtonian Physics, although more accurate in describing what actually happens; or Aristotelian Physics, which catalogs our expectations and our relationship to what happens?

>The numerous amoraim in this gemara, most clearly Rabbi Chuna’s second statement at the end of my quote, assume that when an object falls, it falls down to the ground it is directly over. Not as Newton showed, that a thrown object follows a trajectory, a parabola.

I am sorry, can you explain how you derive this from the Gemara?

“Rabbi Chuna said: Over there is a case where if it were to fall, the ground under it is private domain. Whereas over here if it were to fall, the ground under it was [already] public domain.”

His assumption being that an object in motions still falls straight down, no?

Remember also that this is a blog, and therefore a collection of posts appears with the chronologically last on top, even though the thought is developed by the author in the opposite order.

Could it be that Rav Chuna is just asking about what airspace the object is in? The “if it were to fall” is just an imaginary way of determining that…

Did people really believe that if I shoot an arrow, and then change my mind, the arrow will fall straight down?

As per this post… people really thought that thrown objects “start to fall” and then fall straight down. And recent studies show that even people who catch for a living only compensate for this instinct and don’t fully overcome it. This is our instinct, how humans — even those who intellectually know better — actually relate to the world.

There is no reason to believe Rav Chuna was talking about anything other than the natural philosophy of his day.

An object flies from reshus ha’yochid to reshus ha’rabbim, and before it crosses the boundary, I remember it’s Shabbos — so, “Rabbi Chuna said: Over there is a case where if it were to fall, the ground under it is private domain…”. Why does he say, “if it were to fall”? Why would it fall? Is the assumption that if I stop desiring the object to keep moving, it will fall down immediately? But then the object doesn’t cross into reshus ha’rabbim, and there is no melacha…

So, what’s the point in asking what would happen if the object fell? How is the object going to fall?

To me, the pshat seems to be that Rav Chuna is asking where the object is — in reshus ha’rabbim or rh”y.

You needed modern psychology to tell you how baseball players think. But my intuitive folk psychology tells me that they just catch the ball based on prediction of its trajectory, and if I look at the pictures of ball flying (or watch a baseball match), I see that it flies at an arch. So, why should I take a modern scientist’s word over my instincts about how other people think?

It just seems that the phraseology “if the object were to fall” is much closer in its meaning to “if the object stopped in the air and fell” as opposed to “if the object started on its downward motion”. You can imagine the same lexicon in determining what the citizenship of a child born on an an airplane is: “If the plane were to land, which country would it land?” The assumption is not that when airplane lands, it drops straight down…